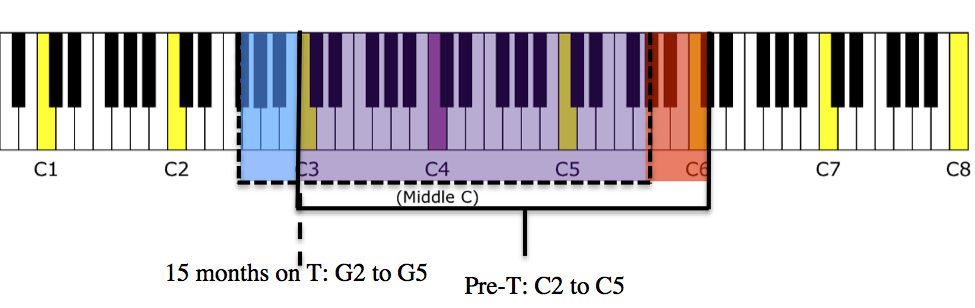

I’ve been taking voice lessons with Laura Hynes for a few years now, beginning well before I started taking testosterone. The piano in her studio is situated below a tall window through which the late afternoon sun illuminates two large mirrors hanging on opposite walls. Mirrors are useful tools for singers, because they allow us to literally see how our bodies make the sounds we’re hearing. While singing is, ultimately, about sound, that visual input can be quite helpful. Unfurling a furrowed brow, relaxing a curved tongue, or releasing tense shoulders can make big differences in the quality of sound a singer makes. Having a mirror lets you check in on yourself; seeing your reflection provides important information as you learn to coordinate your body to produce the most efficient and beautiful sound you can. Before I started T, I could sing from C3 (an octave below middle C) to C6 (two octaves above middle C), the purple and red sections on the diagram below. Since then I’ve gained five half-steps at the bottom (blue section) and lost five half-steps at the top (red section). In addition to the top and bottom of my range changing, the transitions between my registers (or breaks) also shifted down.

Singing Range Pre-T and After 15 Months of Testosterone

“An A?” I asked, not quite registering.

She nodded. “An A, before the lowest you could sing was a C or maybe a B.”

Once it did sink in, I remember catching a glimpse of myself in the mirror. The person looking back at me didn’t look any different than they had at last week’s lesson. But something about me had changed. Up until that point I hadn’t noticed any differences in how I looked, felt, or sounded, whether speaking or singing, since beginning testosterone. People close to me also hadn’t noticed any differences. I knew starting on a lower dose of testosterone meant that the changes would occur more gradually, but without any outward signs of transition, I could only have faith that the hormones were impacting my body in ways that I couldn’t quite see yet. Under my skin, absorbed through my thigh muscle, and transported through my body in my blood, the testosterone I had been injecting had been sending messages to other cells, directing their development and activity. One of the changes it caused was to add to the bulk, to the thickness of my vocal cords. And then that one day, in just a split second, I learned my cords had gotten thick enough, that when I brought them together and passed air through them, I could produce vibrations that moved a bit more slowly than they did the week before, I sang an A.

But the person in the mirror was the same. I still had the same dark brown, almost black, hair, close cropped on the sides and back, longer and thick on top with just a few strands of gray at the temples. My face was still soft and round, boyish. Even before I started T, I was sometimes taken for a teenage boy, though I was close to forty years old. The smile in the mirror was still broad and warm. Thick, dark eyebrows framed sensitive, almost sad, brown eyes. There it was, something in my eyes had changed. Even though I still looked the same, I knew, now, that I was different. That knowing, that revelation, showed itself in my eyes. A brightness, a depth, an awareness. Something had shifted. Maybe it was just knowing that my body had begun to change that gave me a new perspective on myself. I felt profound, almost miraculous joy at discovering this change in my voice. My body was slowly responding to the testosterone I was taking, but the only thing that showed was a twinkle in my eye and an A2 sung in 330 Brooks Hall on the University of Calgary campus. Realizing that my voice change had begun was about much more than just being able to sing a step lower than I had before: it meant this change I had been anticipating for so long was finally, really happening. In the weeks and months that followed, I continued to lose notes at the top of my range and gain them at the bottom, but nothing was as exciting, or as reassuring, as that first time.

Changes in Timbre

While that first shift was an important marker, I came to realize that the changes at the very top and bottom of my range really didn’t make much of a difference in my daily singing life, because I spend very little time singing in the very high or very low parts of my range. There’s actually a great deal of overlap in the notes I could sing pre-T and what I can sing now (the purple section on the diagram). While I’ve always been able to sing in that middle part of my range, the changes in how my voice sounds when I’m singing there have made a far bigger difference than the low notes I’ve gained or the high ones I’ve lost.

Before starting T, I almost always sang in my head voice which was bright and resonant. In adult AMABs (people assigned-male-at-birth) the head voice, sometimes referred to as falsetto, tends to be lighter and more breathy-sounding. Once I started taking testosterone I worried that my head voice would change and sound more like a falsetto. But so far that hasn’t happened. Compared to before, my head voice sounds darker, richer, more complex, and, to my delight, I haven’t lost the clarity that I love so much. I’m incredibly grateful to still have access to this kind of sound. Also, I am absolutely loving the power and vibrancy I’ve gained in my chest voice. Singing there now feels broad and expansive in a way it never did before. It’s not just that I can sing those notes with more volume and more resonance, but it actually feels different in my body. Unlike AMABs going through puberty, the size and shape of my chest cavity have not changed because of testosterone, but it feels like I have more space there. The subtle vibrations I feel in my chest when I sing in that register, along with the fuller and more dynamic sounds I’m producing, are thrilling!

| Negotiating Register Changes While I’ve been happy with the voice changes that have happened so far, and grateful that my head voice is still available to me, there’s also a lot that has been difficult about the process. My voice has gotten much more fragile and more unpredictable. I struggle with it breaking, cracking, and squeaking, and while this can happen in any part of my range, it happens more often around the register changes. When it’s particularly unstable, I can’t help but laugh at myself. You just can’t take yourself too seriously when your voice bears a striking resemblance to a honking goose or Peter Brady singing “Time to change”. |  Christopher Knight (Peter Brady) http://commons.wikimedia.org |

Even with this uncertainty, I try to remember that negotiating register changes is a skill that can be learned, and one in which I’ve already made progress through practice and work in my lessons. It’s also encouraging to remember that those squeaks, breaks, and cracks don’t necessarily mean that I’m doing anything wrong. They are a normal part of the process and are, in fact, signs that my voice is changing. During my lesson with Emily that day I was using my hands to model the movement of my larynx while singing easy glides from five to one to five, when, as we approached my register change, my voice started breaking and cracking. Feeling self-conscious, I said, “It’s landing right in the fuzzy spot for me.”

Emily responded, “That’s good. Fuzzy stuff is great!” Then, after a long pause, continued, “If you try and push away the awkwardness it just gets bigger. So instead, you just revel... You know, you can only be who you are.”

I nodded.

Emily continued, “And that means all the cracks and fissures. I, personally, think they’re the most fascinating part of any voice.”

Vocal Fatigue

Another big change that poses a lot of challenges is that my voice gets tired much more quickly now than it did before. A few things have helped with this. I no longer rely solely on group warm-ups and always warm up on my own prior to rehearsal. During rehearsal if there is a repeated line, or a line that feels too high or too low, I take a vocal break. Using healthy technique, singing with good breath support, and avoiding tension and strain are always important, but these things seem to make even more of a difference now. Most importantly, I try never to push my voice beyond what is comfortable. This is much easier said than done, though, because I love to sing. I want to sing. In rehearsal I’m surrounded by singing voices, and it’s frustrating to have to stop for a while, or hold back.

Even with these strategies, my voice is often tired after a full choir rehearsal. I’ve also found it takes more rest for my voice to get back to normal after a lot of singing. Like most musicians, the Christmas season is an especially busy time of year for me. This year I paid special attention to not over-singing and resting my voice as much as possible between performances, but in the last performance of that season, and for the first time in my life, I just wasn’t able to sing up to my usual standards. It was heartbreaking and sobering.

What makes the difficult parts of this voice change much more challenging is that I don’t know how long they will last and cannot be totally sure that they will ever resolve. There’s growing interest in voice changes among trans singers taking testosterone, but there is not yet much research. There are more and more stories of singers who have successfully transitioned along with continuing stories of singers with persistent vocal problems. I try to be optimistic and stay present-focused, but it’s hard to totally let go of that uncertainty.

Section Assignments

With all of these changes, when it comes to ensemble singing my voice is somewhere between alto and tenor. Singing alto all of the time is too high and singing tenor all of the time is too low. My voice does not fit well into any of the existing categories, and that feels isolating. The in-between position of my voice is often mirrored by my physical location in the choir. When we sit in sections ordered from high to low I am on the low-end of the alto section and the high-end of the tenors. I’m literally right in the middle, perched on an invisible line, with the altos and sopranos lined up on my right and the tenors and basses on my left. On some songs I sing alto and on others I sing tenor, but I don’t really belong in either section. I teeter on the border between the two, not really comfortable or fitting in to either.

Singing and Living Outside of the Binary

The parallels between my voice not fitting in the existing structure and my gender not fitting the binary are striking. I am genderqueer. For me, this means that I am neither a man nor a woman. I am not part-man and part-woman. I do not lie somewhere between the man- and woman- ends of a gender spectrum. I do not move between man and woman. I am not androgynous, and I’m not gender-neutral or gender-free. I exist outside of the binary gender structure, and now, so does my voice.

Singing outside of the existing structure is difficult. Living outside of the gender binary also has painful consequences. I am misgendered and referred to as ‘she’ or ‘her’ or ‘miss’ or ‘ma’am’ every day of my life. I cannot expect that there will be a safe place for me to use the washroom. The washroom issue is magnified by a thousand when it comes to change rooms at the gym. When filling out forms at doctor’s offices, do I check “M” or “F”? When signing up to play softball, will I fill a slot allotted for a “man” or a “woman?” There’s no room for anything else. After top surgery, what will happen if I take my shirt off at the beach and reveal the long, pink scars on my chest?

Despite the risks and trials associated with living outside of the gender binary, the identity itself, being genderqueer, feels good and right. It fits. Discovering and embracing this identity has been revolutionary for me. I feel serene and strong and powerful and sexy and beautiful and handsome. I feel safe and vulnerable and open and real. It just feels right.

Singing outside of the boxes, though, that feels alienating and lonely. I want to be comfortable singing a voice part. I don’t want my voice to get tired part way through rehearsal. I don’t want to feel like the notes I’m supposed to sing are an uncomfortable stretch or reach. I want to have control over my voice. I’m tired of these challenges getting in the way of singing. There are only so many jokes I can make about being “trans-sectional” or “section-queer.” Poking fun at myself can alleviate some stress, but not being able to comfortably sing in any section and having limited stability and stamina are wearing on me.

One of the things I love most about singing in a choir is the intensely personal way it allows me to connect with other singers and listeners. It is so intimate because we use our bodies to produce sound and every voice impacts an ensemble’s sound. In Western music, the role of each section is prescribed by (usually) written parts. Because of this, not fitting in to any of the sections is especially painful. What is my place in the choir? What is my role? Getting too wrapped up in an identity can be problematic, and it would be easy for me to ask to be assigned to the tenor section full-time, but that wouldn’t really make a difference if my voice is still somewhere in-between. This kind of not-fitting-in is especially painful because it is connected to my voice, something that has always brought me great joy and pride, and also because I already experience so much alienation and exclusion because I’m genderqueer.

I knew that there would be a lot of uncertainty in my voice change when I decided to begin taking T. I knew that I’d have no way of predicting how low my voice would get. I expected that the transition would include vocal fragility and fatigue. I knew that I could not know for sure, what that would be like, how long the transition would last, or what I might sound like afterwards.

Knowing that the future holds uncertainty did not prepare me to live with it, inside of it, slipping and sliding around it and through it. The doubt feels like a low, rumbling drone. Sometimes it’s louder and sometimes it’s softer. Sometimes, when my life is full, I don’t hear it at all. Sometimes it’s so quiet that I’m not even sure it’s there, but then, before I even hear it, I feel the vibrations in my bones and in my chest, and I know it’s back. Or maybe it never really left? It’s hard to know. Other times it’s so loud that it drowns out everything, it occupies every part of my consciousness, squeezing out other thoughts and ideas and reassurances. My eardrums pound in time with the beat and my ears hurt. My biggest worry is that I’ll forever be stuck in this middle space, between sections, with a fragile voice full of breaks and unable to endure a full rehearsal.

But then I pause, breathe, and look around from my spot right in the middle of the choir. From this vantage point, I can see and hear everyone; to my right are all of the sopranos and altos and to my left are all of the tenors and basses. The conductor is right in front of me. While my voice doesn’t fit neatly with the singers on either my right or my left, it allows me to float between them. Maybe I’m both, maybe I’m neither, maybe it depends on the moment. I pull up some recordings and listen to myself pre-T and today. (Check out this post to listen.) Hearing the two so close together brings out both the contrast and the underlying continuity. At this moment in my transition it feels like I have access to the best of many different worlds. I’m just as happy singing the alto line in Palestrina’s Sicut Cervus (ca 1525 – 1594) with glorious resonance and ping as I am learning to blend my head and chest voice in Sorry-Grateful from Steven Sondheim’s Company (1970). I’ve maintained a three octave range. Despite the chaos of different hormones, thickening cords, additional warm-ups, and unstable breaks shifting and rupturing below me, I’m reassured to still feel connected with my voice as I sing through the cracks and try to embrace the fuzzy stuff.

Curious about what my voice sounds like?

Click here to go to a brief presentation that includes examples of my singing voice from different points in the first 15 months of my transition.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed