When you type “FTM transition” into an online search engine you will find pages upon pages of links, including information on testosterone therapy. One particular genre of online resource is the “transition video,” a mostly DIY undertaking in which people assigned female at birth (AFAB) talk about and document their varied experiences taking testosterone. Transition videos really are quite remarkable; in the time it takes to microwave a bag of popcorn, you are able to witness the physical changes that occur in a person taking testosterone over the course of days, weeks, months, and years.

One of the most noticeable changes that results from taking T is also often most sought after: the deepening of the voice. While the potential of a lower voice is incredibly appealing to me, it also makes me very anxious.

The possibility of a lower voice is exciting, because the pitch of my voice immediately indicates to the world that I am a woman, even though I am not one. I am genderqueer. This means that I am neither a woman or a man. At first glance people may not be totally sure what to make of me, but as soon as I speak they decide that I am a woman based on the pitch of my voice. Constantly being misgendered as a woman is extraordinarily painful and invalidating. I am thrilled at the possibility of having a lower voice, but my decision to start T is not a simple one.

My choice is complicated because I am an avid amateur singer, and we do not yet have much systematic information about how T affects the voice. I’ve dabbled in doing solos, but my real passion is singing in ensembles. I’ve sung in choirs pretty consistently since I was about ten years old. Looking back over the last almost thirty years of my life I don’t think there was a period of more than a year when I was not singing in a choir. I’ve been a sucker for harmony for as long as I can remember!

While all creative expression requires risk taking and vulnerability, singing is intensely personal in a very concrete way. I am, quite literally, my own instrument. I use my body to produce the sounds I share with the world. And an ensemble’s sound depends on each and every voice. Singing well as an ensemble is not just about hitting the right notes at the right times and singing in tune, it requires intense listening to each other’s voices and your own, it is breathing together, forming and transitioning between vowels in sync, matching tone, agreeing on emphasis, dynamics, and articulation, it requires connecting with the spirit of a work, conveying it to your audience, and so much more.

The work may seem demanding, and the stakes high. It is and they are, but the reward is beyond compare. When singing in a choir we share of ourselves in a very fundamental way and we support the other singers around us as they do the same. The mutual vulnerability and support inherent in coming together to sing can cultivate connections among singers that elevate the music making experience. I’ve had these sorts of connections with folks I’ve been singing with for decades, those who I’ve been rehearsing and performing with for just a few months, and even in groups that I only sing with once. Singing has fostered some of the most important relationships in my life. Through singing I’ve met, to quote a mentor, Tony Leach, “some of the best people this side of heaven.”

Singing in a choir is when I feel the most alive, the most connected with the core essence of myself, with my fellow musicians, and with the world around me. Singing makes my life complete and it is hard to imagine my life without it. If my ability to sing were compromised, it is also hard to imagine anything else that would allow me to connect with others, to give of myself, and to experience the sheer joy and power of music in quite the same way. This is why the decision to start T is so difficult for me.

The possibility of a lower voice is exciting, because the pitch of my voice immediately indicates to the world that I am a woman, even though I am not one. I am genderqueer. This means that I am neither a woman or a man. At first glance people may not be totally sure what to make of me, but as soon as I speak they decide that I am a woman based on the pitch of my voice. Constantly being misgendered as a woman is extraordinarily painful and invalidating. I am thrilled at the possibility of having a lower voice, but my decision to start T is not a simple one.

My choice is complicated because I am an avid amateur singer, and we do not yet have much systematic information about how T affects the voice. I’ve dabbled in doing solos, but my real passion is singing in ensembles. I’ve sung in choirs pretty consistently since I was about ten years old. Looking back over the last almost thirty years of my life I don’t think there was a period of more than a year when I was not singing in a choir. I’ve been a sucker for harmony for as long as I can remember!

While all creative expression requires risk taking and vulnerability, singing is intensely personal in a very concrete way. I am, quite literally, my own instrument. I use my body to produce the sounds I share with the world. And an ensemble’s sound depends on each and every voice. Singing well as an ensemble is not just about hitting the right notes at the right times and singing in tune, it requires intense listening to each other’s voices and your own, it is breathing together, forming and transitioning between vowels in sync, matching tone, agreeing on emphasis, dynamics, and articulation, it requires connecting with the spirit of a work, conveying it to your audience, and so much more.

The work may seem demanding, and the stakes high. It is and they are, but the reward is beyond compare. When singing in a choir we share of ourselves in a very fundamental way and we support the other singers around us as they do the same. The mutual vulnerability and support inherent in coming together to sing can cultivate connections among singers that elevate the music making experience. I’ve had these sorts of connections with folks I’ve been singing with for decades, those who I’ve been rehearsing and performing with for just a few months, and even in groups that I only sing with once. Singing has fostered some of the most important relationships in my life. Through singing I’ve met, to quote a mentor, Tony Leach, “some of the best people this side of heaven.”

Singing in a choir is when I feel the most alive, the most connected with the core essence of myself, with my fellow musicians, and with the world around me. Singing makes my life complete and it is hard to imagine my life without it. If my ability to sing were compromised, it is also hard to imagine anything else that would allow me to connect with others, to give of myself, and to experience the sheer joy and power of music in quite the same way. This is why the decision to start T is so difficult for me.

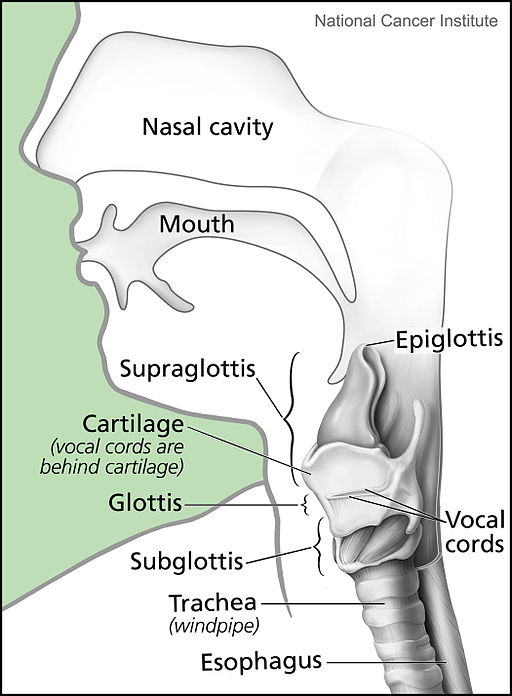

| Because singing is such a fundamental part of my life, the possibility of testosterone negatively affecting my voice is very frightening. In order to understand how T affects the voices of people who transition, I first needed to learn more about how human voices work. I learned that we produce sound when air passes between and vibrates closed vocal cords, and that vocal cords are mucous membranes stretched across the larynx (or voice box), which is located on top of the trachea. The pitch of the sounds we make is determined by the tension in our vocal cords as well as their size. We control the tension in our cords by contracting and releasing them to make higher and lower sounds. In addition, people assigned male at birth (AMAB) tend to have longer and thicker vocal cords than AFABs, and thus lower voices. Children’s voices do not vary by sex assigned at birth, but when children assigned male at birth (AMAB) go through puberty, their cords get thicker and longer, their voice boxes get larger |

and tilt forward (forming the Adam's Apple) and their voices get deeper. This voice change is accompanied by a period of cracking, squeaking, and instability before it settles. Lots is known about AMAB voice changes because there have been decades of data collection and research into how this process works. AFAB children’s vocal cords also grow and they experience a voice change, but the change tends to be more subtle.

When AFABs take testosterone, we experience similar physical changes to what happens when AMAB’s voices change during puberty. Our vocal cords also get thicker, which causes our voices to drop, but there are some important differences, too. Often AFABs who transition increase their levels of testosterone from the lower levels typical for us to higher levels typical of AMABs, fairly quickly, often in less than a year. Wanting to see changes quickly is completely understandable given the gender dysphoria that so many trans folks experience. The problem is, the fast growth can be difficult for the delicate structures of our vocal cords to adjust to. Another important difference has to do with age. Because AMABs typically experience these changes during adolescence, they have more flexibility in their larynxes, and their bodies grow in size along side their growing cords. AFABs typically begin testosterone therapy when we are older, so our larynxes are less flexible and do not usually grow substantially.

The rapid growth of vocal cords and lack of room for growing cords among trans singers can lead to a phenomenon that Alexandros Constantis calls “entrapped vocality” (Constantis 2008 and 2013), which is when the voice is persistently weak, hoarse, and lacking in control and power. This is not the same as the instability AMABs experience when their voices change, because, in most cases, AMABs voices eventually settle. But for trans singers who have this problem, these symptoms persist.

What makes this issue worrisome for me and other singers who are AFAB is there is no systematic research about how frequently these problems occur among AFAB people who take testosterone. Initially the belief was that AFABs who took testosterone would automatically have lower voices and successful vocal transitions. More recent work recognizes that this is not always the case, though. Commentary ranges from the fairly measured:

The present study examined whether the voice change in female-to-male transsexuals is

indeed as straightforward as it is assumed. Results suggest that the voice change is not always

totally unproblematic.(Van Borsel et. al, 2000, p.1)

To the far more disconcerting:

Professional or amateur singers and speakers should be warned that frequently voice changes

occur that may be significantly detrimental to vocal performance. These changes are both

unpredictable and irreversible. (Gorton, et al., 2005,p.59)

While formal research is very limited, it is certainly not the only source for information about how people’s voices change when they take T. I learned quite a lot searching the web, reading personal accounts of people who were taking T, and watching those transition videos I mentioned earlier. It was really those blogs, pictures, and videos, what they showed about the changes that happen when you take T, and people’s experiences going through those transformations that got me thinking seriously about my own journey. It was there that I saw and heard countless people change before my eyes. They got more hair, fewer curves, their faces became less round, and, of course, their voices got lower.

These online resources also contributed to my concern about how T would affect my singing voice. While there are lots of folks who have had incredible and empowering experiences with their physical transitions, many have also experienced lots of problems with their voices and ended up with little to no ability to sing. That outcome is almost unthinkable to me.

Where Does That Leave Me?

Drawing on the tiny body of research on singers who transition and what we know about AMAB’s vocal transitions in adolescence, a few recommendations have been suggested.

Despite these recommendations, there is still so much that is unknown. How frequently do people who transition with T experience problems with their voices and how often does it go smoothly? Are we talking 50–50 odds? Better? Worse? How much of a difference does following these recommendations make?

I’ve been singing for my whole life, I’ve spent years learning how to breathe correctly and use my voice in a healthy way, but how much difference will all that training really make? Can the sorts of problems people who transition face be overcome by working with teachers and making a gradual transition, or does it have more to do with anatomical issues over which I have no control? Will the process be similar to what AMABs go through? How will it be different?

Having a lower voice would make navigating the everyday world considerably better for me, but am I willing to risk my ability to sing being severely compromised or maybe even totally lost? On the other hand, am I willing to continue living in a body that consistently leads people to misgender me as a woman? Am I willing to continue to be made invisible, to have my identity erased on a daily basis?

When making any sort of big decision, I like to be as informed as possible. I’ve read pretty close to everything that has been published about this subject; I’ve watched films, documentaries and transition videos, I’ve read articles, blogs, and websites, I’ve consulted with professional singers and voice teachers, and I’ve talked to friends who have transitioned. The conclusion that I’ve come to is that we just don’t know very much about how these sorts of transitions work. There’s no systematic information about basics like what actually happens to the vocal cords and singing voices of people who transition. No one knows how often these transitions go smoothly, and how often they don’t. And there’s no conclusive information about how effective the recommended approaches to successful voice transitions actually are.

It comes down to whether I’m willing to take that risk. Whether I’m willing to go down a path that could bring my voice more in line with my genderqueer self, thus engendering deep peace and comfort in my body, but that could also seriously injure my voice, thus severely limiting my ability to sing.

When AFABs take testosterone, we experience similar physical changes to what happens when AMAB’s voices change during puberty. Our vocal cords also get thicker, which causes our voices to drop, but there are some important differences, too. Often AFABs who transition increase their levels of testosterone from the lower levels typical for us to higher levels typical of AMABs, fairly quickly, often in less than a year. Wanting to see changes quickly is completely understandable given the gender dysphoria that so many trans folks experience. The problem is, the fast growth can be difficult for the delicate structures of our vocal cords to adjust to. Another important difference has to do with age. Because AMABs typically experience these changes during adolescence, they have more flexibility in their larynxes, and their bodies grow in size along side their growing cords. AFABs typically begin testosterone therapy when we are older, so our larynxes are less flexible and do not usually grow substantially.

The rapid growth of vocal cords and lack of room for growing cords among trans singers can lead to a phenomenon that Alexandros Constantis calls “entrapped vocality” (Constantis 2008 and 2013), which is when the voice is persistently weak, hoarse, and lacking in control and power. This is not the same as the instability AMABs experience when their voices change, because, in most cases, AMABs voices eventually settle. But for trans singers who have this problem, these symptoms persist.

What makes this issue worrisome for me and other singers who are AFAB is there is no systematic research about how frequently these problems occur among AFAB people who take testosterone. Initially the belief was that AFABs who took testosterone would automatically have lower voices and successful vocal transitions. More recent work recognizes that this is not always the case, though. Commentary ranges from the fairly measured:

The present study examined whether the voice change in female-to-male transsexuals is

indeed as straightforward as it is assumed. Results suggest that the voice change is not always

totally unproblematic.(Van Borsel et. al, 2000, p.1)

To the far more disconcerting:

Professional or amateur singers and speakers should be warned that frequently voice changes

occur that may be significantly detrimental to vocal performance. These changes are both

unpredictable and irreversible. (Gorton, et al., 2005,p.59)

While formal research is very limited, it is certainly not the only source for information about how people’s voices change when they take T. I learned quite a lot searching the web, reading personal accounts of people who were taking T, and watching those transition videos I mentioned earlier. It was really those blogs, pictures, and videos, what they showed about the changes that happen when you take T, and people’s experiences going through those transformations that got me thinking seriously about my own journey. It was there that I saw and heard countless people change before my eyes. They got more hair, fewer curves, their faces became less round, and, of course, their voices got lower.

These online resources also contributed to my concern about how T would affect my singing voice. While there are lots of folks who have had incredible and empowering experiences with their physical transitions, many have also experienced lots of problems with their voices and ended up with little to no ability to sing. That outcome is almost unthinkable to me.

Where Does That Leave Me?

Drawing on the tiny body of research on singers who transition and what we know about AMAB’s vocal transitions in adolescence, a few recommendations have been suggested.

- Transition slowly,

- Get support from a professional speech therapist and voice coach, and

- Sing throughout your transition.

Despite these recommendations, there is still so much that is unknown. How frequently do people who transition with T experience problems with their voices and how often does it go smoothly? Are we talking 50–50 odds? Better? Worse? How much of a difference does following these recommendations make?

I’ve been singing for my whole life, I’ve spent years learning how to breathe correctly and use my voice in a healthy way, but how much difference will all that training really make? Can the sorts of problems people who transition face be overcome by working with teachers and making a gradual transition, or does it have more to do with anatomical issues over which I have no control? Will the process be similar to what AMABs go through? How will it be different?

Having a lower voice would make navigating the everyday world considerably better for me, but am I willing to risk my ability to sing being severely compromised or maybe even totally lost? On the other hand, am I willing to continue living in a body that consistently leads people to misgender me as a woman? Am I willing to continue to be made invisible, to have my identity erased on a daily basis?

When making any sort of big decision, I like to be as informed as possible. I’ve read pretty close to everything that has been published about this subject; I’ve watched films, documentaries and transition videos, I’ve read articles, blogs, and websites, I’ve consulted with professional singers and voice teachers, and I’ve talked to friends who have transitioned. The conclusion that I’ve come to is that we just don’t know very much about how these sorts of transitions work. There’s no systematic information about basics like what actually happens to the vocal cords and singing voices of people who transition. No one knows how often these transitions go smoothly, and how often they don’t. And there’s no conclusive information about how effective the recommended approaches to successful voice transitions actually are.

It comes down to whether I’m willing to take that risk. Whether I’m willing to go down a path that could bring my voice more in line with my genderqueer self, thus engendering deep peace and comfort in my body, but that could also seriously injure my voice, thus severely limiting my ability to sing.

| I have decided that I cannot continue living my life this way when there is an alternative. Despite the risks and the unknowns, taking testosterone is something I need to do. I’ve come to think of taking T as a form of radical self-care. I am committed to loving myself deeply. In order to care for my whole self, my mind, body, and spirit, I need to take these steps. I don’t know exactly what my future will look or sound like, but I’m very much looking forward to finding out! |

Since I will be taking these steps and there is so little research on vocal transitions in trans singers, I will be working with my voice teacher, Laura Hynes, to conduct a study documenting how my singing voice changes over the course of my transition. We expect to collect data for a year or two, so it will be a while before we have results available, but I’m eagerly anticipating the process.

References:

Constansis, A. (2008). The Changing Female-To-Male (FTM) Voice. Radical Musicology, 3.

Constansis, A. (2013) The Female-to-Male (FTM) Singing Voice and its Interaction with Queer Theory: Roles and Interdependency. Transposition, 3,2 -22.

Gorton R., Buth J., and Spade, D., (2005) Medical Therapy and Health Maintenance for Transgender Men: A Guide For Health Care Providers. Lyon-Martin Women’s Health Services. San Francisco, CA.

Van Borsel, J., De Cuypere, G., Rubens, R., Destaerke, B. (2000). Voice Problems in female-to-male transsexuals. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 35 (3), 427–442

If you liked this post,

References:

Constansis, A. (2008). The Changing Female-To-Male (FTM) Voice. Radical Musicology, 3.

Constansis, A. (2013) The Female-to-Male (FTM) Singing Voice and its Interaction with Queer Theory: Roles and Interdependency. Transposition, 3,2 -22.

Gorton R., Buth J., and Spade, D., (2005) Medical Therapy and Health Maintenance for Transgender Men: A Guide For Health Care Providers. Lyon-Martin Women’s Health Services. San Francisco, CA.

Van Borsel, J., De Cuypere, G., Rubens, R., Destaerke, B. (2000). Voice Problems in female-to-male transsexuals. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 35 (3), 427–442

If you liked this post,

RSS Feed

RSS Feed